Research Line 3:

Stereotypes and Biases

The superficial cues often employed in character judgment, such as attire or facial features, lay bare the biases nestled within social perceptions. For instance, findings show how masculine facial features or expensive attire can lead to attributions of higher competence (Oh et al., 2019 Psychol Sci; Oh et al., 2020 Nat Human Behav). This line of work sometimes employs a data-driven modeling approach (Oh et al., 2019, Vis Res) to identify the visual information responsible for forming face-based trait impressions, such as perceived intelligence and warmth (Todorov & Oh, 2021, Adv Exp Soc Psychol).

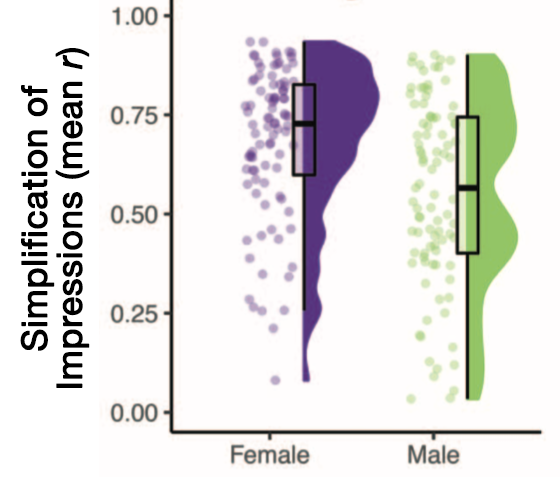

Impressions of women from faces tend to be more compressed than those of men. This compression means that people often rely heavily on one or two apparent traits to make broader assumptions about a woman's character, reflecting stronger preconceptions. Indeed, individuals who strongly endorse stereotypes tend to have more pronounced biases in their judgments (Oh et al., 2020 J Exp Psychol Gen).

Impressions of women from faces tend to be more compressed than those of men. This compression means that people often rely heavily on one or two apparent traits to make broader assumptions about a woman's character, reflecting stronger preconceptions. Indeed, individuals who strongly endorse stereotypes tend to have more pronounced biases in their judgments (Oh et al., 2020 J Exp Psychol Gen).

People have more simplified impressions of women than of men. In this plot, the level of impression simplification is indexed by the level of all pairwise correlations across specific trait impressions (e.g., impression of likeability). Each dot represents the level of correlations between a pair of impression ratings (e.g., correlation between the impression of likeability and the impression of dominance across all participants). (from Oh et al., 2020 J Exp Psychol: Gen)

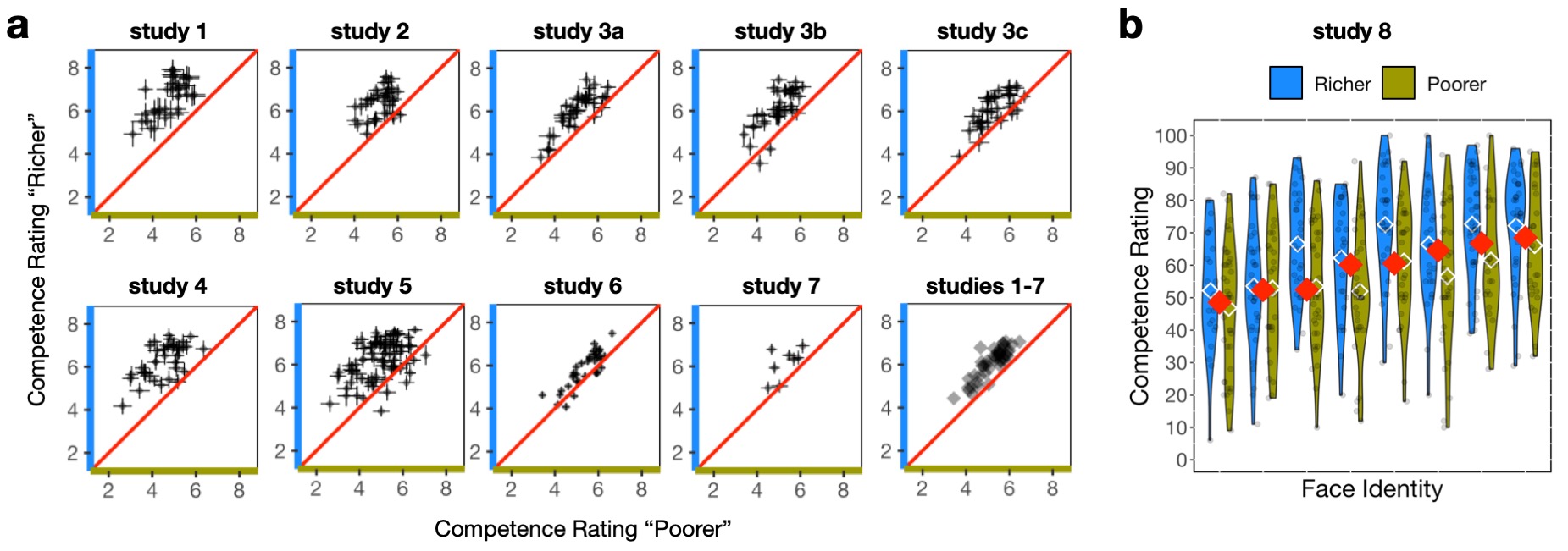

Participants across studies rated faces paired with “richer” clothes as more competent than the same faces paired with “poorer” clothes. These participants include in-person Princeton University sample, older adults sample recruited in a mall in New Jersey, and online participants that were more diverse in age and other demographics.

a: Participants were given various measures that discouraged them to rely on the clothes while judging competence of other individuals. x=mean competence rating of a face with it is paired with “poorer” clothes, y=mean competence rating of a face with it is paired with “richer” clothes; each dot = each face.

b: Participants were promised $100 to “accurately” judge how competent each person looked (that is, completely ignore the effect of the clothes). Strikingly, this did not change the biases induced by economic status cues in the clothes. x = each face; y = mean competence rating; each color = economic status of clothes paired with the face.(from Oh et al., 2020 Nat Hum Behav)

Expanding on this, the research delves into how the socially marginalized might resist the biasing forces in intuitive judgments. A project, in collaboration, investigates whether economic status cues in attire can serve as tools to counter societal stereotypes, especially among women and racial minorities. Utilizing real-world data and immersive virtual reality, the aim is to discern if sartorial choices stem from strategic counteraction against negative stereotypes. This ongoing research is expected to reshape understanding of self-presentation strategies in response to stereotypes, holding practical implications for reducing biases in daily interactions.